In this first tutorial we will introduce the main tools we will be working with throughout the rest of the course. Although very basic and seemingly abstract, everything showed here will become the basis on top of which we will build more sophisticated (and fun) tasks. But, before, let us get to know the tools that will give us data super-powers.

Open Source¶

This course will introduce you to a series of computational tools that make the life of the Data Scientist possible, and much easier. All of them are open-source, which means the creators of these pieces of software have made available the source code for people to use it, study it, modify it, and re-distribute it. This has allowed a large eco-system that today represents the best option for scientific computing, and is used widely both in industry and academia. Thanks to this, this course can be taught with entirely freely available tools that you can install in any of your computers.

If you want to learn more about open-source and free software, here are a few links:

- [Video]: brief explanation of open source.

- [Book] The Cathedral and the Bazaar: classic book, freely available, that documents the benefits and history of open-source software.

Jupyter Notebook¶

The main computational tool you will be using during this course is the Jupyter notebook. Notebooks are a convenient way to thread text, code and the output it produces in a simple file that you can then share, edit and modify. You can think of notebooks as the Word document of Data Scientists, just better.

Start a notebook¶

In order to begin a notebook session, you need to do it from what is called the command line, a terminal window that allows you to interact with your computer through written commands. This is how you can fire up a terminal:

- If you are on a Windows computer, you can start PowerShell from the Start menu (

cmd prompt). - On a Mac, fire up the Terminal.app utility.

- In Linux, use any of the terminals available.

Then type the following command

> source activate gdsNOTE: ignore source if you are on Windows and simply type activate gds.

Then launch Jupyter by typing on the same terminal:

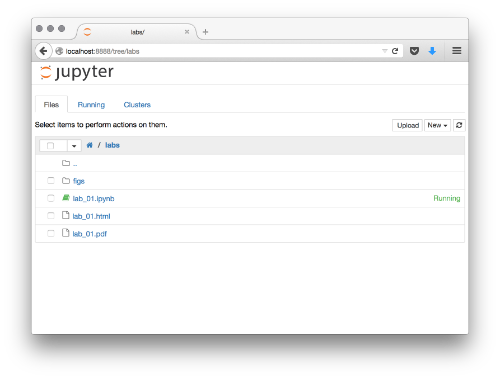

> jupyter notebookThis should bring up a browser window with a home page that looks more or less like this (although with a different list of files probably):

Navigate until the folder where you have placed the lab_01.ipynb file for this tutorial and click on it. This will open the notebook on a different tab. You are now on the interactive version of the notebook!

When you are finished with the session, you can save the notebook with File -> Save and Checkpoint. Everything you do on the notebook (text, code and output) is saved into an .ipynb file that you can open later, share, etc.

Cells¶

The main building block of notebooks are cells. These are chunks of the same time of content which can be cut, pasted, and moved around in a notebook. Cells can be of two types:

- Text, like the one where this is written.

- Code, like the following one below:

# This is a code cell

You can create a new cell by clicking Insert -> Cell Above/Below in the top menu. By default, this will be a code cell, but you can change that on the Cell -> Cell Type menu. Choose Markdown for a text cell. Once a new cell is created, you can edit it by clicking on it, which will create the cursor bar inside for you to start typing.

Pro tip!: cells can also be created with shortcuts. If you press <escape> and then b (a), a new cell will be created below (above). There is a whole bunch of shortcuts you can explore by pressing <escape> and h (press <escape> again to leave the help).

Code and its output¶

A particularly useful feature of notebooks is that you can save, in the same place, the code you use to generate any output (tables, figures, etc.). As an example, the cell below contains a snipet of Python that returns a printed statement. This statement is then printed below and recorded in the notebook as output:

print("Hello world!!!")

Note also how the notebook has automatic syntax highlighting support for Python. This makes the code much more readable and understandable. More on Python below.

Markdown¶

Text cells in a notebook use the Github Flavored Markdown markup language. This means you can write plain text with some rules and the notebook renders a more visually appealing version of it. Let's see some examples:

- BOLD:

This is **bold**.

Is rendered:

This is bold.

- ITALIC:

This is *italic*.

Is rendered:

This is italic.

- LISTS:

You can create unnumbered lists:

* Item 1

* Item 2

* ...Which will produce:

- Item 1

- Item 2

- ...

Or you can create numbered lists:

1. First element

1. Second element

1. ...And get:

- First element

- Second element

- ...

Note that you don't have to write the actual number of the element, just using 1. always produces a numbered list.

You can also nest lists:

* First unnumbered element, which can be split into:

1. One numbered element

2. Another numbered element

* Second element.

* ...First unnumbered element, which can be split into:

- One numbered element

- Another numbered element

Second element.

- ...

This creates many oportunities to combine things nicely.

- LINKS

You can easily create hyperlinks, for example to [WikiPedia](https://www.wikipedia.org/).

You can easily create hyperlinks, for example to WikiPedia.

- HEADINGS: including

#before a line causes it to render a heading.

# This is Header 1

Turns into:

This is Header 1¶

## This is Header 2

Turns into:

This is Header 2¶

### This is Header 3

Turns into:

This is Header 3¶

And so on...

You can see a more in detail introduction in the following links:

Rich content in a notebook¶

Notebooks can also include rich content from the web. For that, we need to import the display module:

import IPython.display as display

This makes available additional functionality that allows us to embed rich content. For example, we can include a YouTube clip easily by passing it's ID:

display.YouTubeVideo('iinQDhsdE9s')

Or we can pass standard HTML code:

display.HTML("""<table>

<tr>

<th>Header 1</th>

<th>Header 2</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row 1, cell 1</td>

<td>row 1, cell 2</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row 2, cell 1</td>

<td>row 2, cell 2</td>

</tr>

</table>""")

Note that this opens the door for including a large number of elements from the web, as an iframe is also allowed. For example, interactive maps can be included:

osm = """

<iframe width="425" height="350" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" marginheight="0" marginwidth="0" src="http://www.openstreetmap.org/export/embed.html?bbox=-2.9662737250328064%2C53.400500637844594%2C-2.964626848697662%2C53.402550738394034&layer=mapnik" style="border: 1px solid black"></iframe><br/><small><a href="http://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=19/53.40153/-2.96545">View Larger Map</a></small>

"""

display.HTML(osm)

Or sound content:

sound = '''

<iframe width="100%" height="450" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/178720725&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true"></iframe>

'''

display.HTML(sound)

A more thorough exploration of them is available in this notebook.

Exercise to work on your own¶

Try to reproduce, using markdown and the different tools the notebook affords you, the following WikiPedia entry:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chocolate_chip_cookie_dough_ice_cream

display.IFrame('https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chocolate_chip_cookie_dough_ice_cream',

700, 500)

Pay special attention in getting the bold, italics, links, headlines and lists correctly formated. Bonus if you manage to insert the image as well!

Python¶

Although we will have a look at other programs, the main bulk of the course relies on the Python programming language. Python is a high-level programming language widely used today. To give a couple of examples of its relevance, it is underlying most of the Dropbox systems, but also heavily used to control satellites at NASA. A great deal of Science is also done in Python, from research in astronomy at UC Berkley, to courses in economics by Nobel Prize Professors.

This course uses Python because it has emerged as one of the main and most solid options for Data Science, together with other free alternatives such as R. Python is widely used for data processing and analysis both in academia and in industry. There is a vibrant and growing scientific community (example and example), working at both universities and companies, that supports and enhances its capabilities for data analysis by providing new and refining existing extensions (a.ka.a. libraries, see below). In the geospatial world, Python is also very widely adopted, being the selected language for scripting in both ArcGIS and QGIS. All of this means that, whether you are thinking of continuing in Higher Education or trying to find a job in industry, Python will be an importan asset that employers will significantly value.

Being a high-level language means that the code can be "dynamically interpreted", which means it is run on-the-fly without the need to be compiled. This is in contrast to "low-level" programming languages, which first need to be converted into machine code (i.e. compiled) before they can be run. With Python, one does not need to worry about compilation and can just write code, evaluate, fix it, re-evaluate it, etc. in a quick cycle, making it a very productive tool. The rest of this tutorial covers some of the basic elements of the language, from conventions like how to comment your code, to the basic data structures available.

The rest of the tutorial is partly inspired by the introductory lesson in this course by Lorena Barba's group.

Python libraries¶

The standard Python language includes some data structures (e.g. lists, dictionaries, etc. See below) and allows many basic operations (e.g. sum, product, etc.). For example, right out of the box, and without any further action needed, you can use Python as a calculator:

3 + 5

2. / 3

(3 + 5) * 2. / 3

However, the strength of Python as a data analysis tool comes from the extensions provided separately that add functionality and provide access to much more sophisticated data structures and functions. These come in the form of packages, or libraries, that once installed need to be imported into a session.

In this course, we will be using many of the core libraries of what has been called the "PyData stack", the set of libraries that make Python a full-fledge system for Data Science. We will introduce them gradually as we need them for particular tasks but, for now, let us have a look at the foundational library, numpy (short for numerical Python). Importing it is simple:

import numpy as np # we rename it in the session as `np` by convention

Note how we import it and rename it in the session, from numpy to np, which is shorter and more convenient.

Note also how comments work in Python: everything in a line after the # sign is ignored by Python when it evaluates the code. This allows you to insert comments that Python will ignore but that can help you and others better understand the code.

Once imports are out of the way, let us start exploring what we can do with numpy. One of the easiest tasks is to create a sequence of numbers:

seq = np.arange(10)

seq

The first thing to note is that, in line 1, we create the sequence by calling the function arange and assign it to an object called seq (it could have been called anything else, pick your favorite) and, in line 2, we have it printed as the output of the cell.

Another interesting feature is how, since we are calling a numpy function called arange by adding np. in front. This is to note that the function comes explicitly from numpy. To find out how necessary this is, you can try generating the sequence without np:

seq = arange(10)

seq

What you get instead is an error, also called a "traceback". In particular, Python is telling that it cannot find a function named arange in the core library. This is because that particular function is only available in numpy.

Variables¶

A basic feature of Python is the ability to assign a name to different "things", or objects. These can also be called sometimes "variables". We have already seen that in the example above but, to make it more explicit, let us make it even simpler. For example, an object can be a single number:

a = 3

Or a name, also called "string":

b = 'Hello World'

You can check what type an object is also easily:

type(a)

int is short for "integer" which, roughly speaking, means an whole number. If you want to save a number with decimals, you will be using floats:

c = 1.5

type(c)

As mentioned, what we understand as letters in a wide sense (spaces and other signs count too) is called "strings" (str in short):

type(b)

Help¶

A very handy feature of Python is the ability to access on-the-spot help for its different functions. This means that you can check what a function is supposed to do, or how to access it, right inside your Python session. Of course, this also works handsomely inside a notebook. There are a couple of ways to access the help.

Take the numpy function arange that we have used above. The easiest way to check interactively how to use it is by:

np.arange?

As you can see, this brings up a sub-window in the browser with all the information you need.

If, for whatever reason, you needed to print that info into the notebook itself, you can do the following:

help(np.arange)

Control flow (a.k.a. for loops and if statements)¶

Although this does not intend to be a comprehensive introduction to computer programming or general purpose Python (check the references for that, in particular Allen Downey's book), it is important to be aware of two building blocks of almost any computer program: for loops and if statements. It is possible that you will never require them for this course, as all that is used here is based on existing methods and functions, but it is always useful to know they exist and to be able to recognize them. They can also come in very handy in cases where you some extra functionality out of standard methods. Without further ado, let us have a look and the two single most relevant tools of computer programming.

forloops

These allow you to repeat a particular action or task over a sequence. As an example, you can print your name ten times without having to type it yourself every single time:

for i in np.arange(10):

print 'my name'

Note a couple of features in the loop:

- You loop over a sequence, in this particular case the sequence of ten numbers created by

np.arange(10). - In every step, for every element of the sequence in this case, you repeat an action. Here we are printing the same text,

my name. - Although not used in this simple loop, each of the elements you loop over can be accessed inside the loop. This can be irrelevant, as in the loop above, or extremely useful, it depends on the context. For example, see a case where you use the value of the sequence in each step:

for i in np.arange(10):

print "I am at step ", i

One more note: for convention, we are calling the element of the sequence i, but this could be named anything. In fact, in many cases, more meaningful names make code much more readable. For example, you could think of a re-write of the loop above as:

for step in np.arange(10):

print "I am at step ", step

ifstatements

We have just seen how for loops allow you to repeat an action over a sequence. In the case of if statements, these allow you to select or restrict such actions to only those cases that meet a condition(s) you specify in the statement.

For example, if you think of the loops written above, you might want to only print those that are odd, skipping those that are even:

for i in np.arange(10):

if i%2:

print i

Ignore for the moment the part i%2, just remember this is one way Python has to check if a number is odd. The important bit in this loop, as compared to the simpler one above, is that we are using an if statement to select only those candidates that meet the condition. In other words, what we are doing it looping over every number in the sequence from zero to nine (for i in np.arange(10)) and checking if they are even or odd (if i%2). If they meet the condition, they are odd, then we proceed and print them on the screen.

A full if statement also allows for an action to be taken if the original condition is not satisfied. This is called an "ifelse" statement. For example, you can think of a loop that prints the type of each number in a sequence:

for i in np.arange(10):

# Check if it is odd

if i%2:

print i, ' is odd'

# If not odd (even), then do the following

else:

print i, ' is even'

Data structures¶

The standard python you can access without importing any additional libraries contains a few core data structures that is very handy to know. Most of data analysis is done on top of other structures specifically designed for the purpose (numpy arrays and pandas dataframes, mostly. See the following sessions for more details), but some understanding of these core Python structures is very useful. In this context, we will look at three: values, lists, and dictionaries.

- Values: these are the most basic elements to organize data and information in Python. You can think of them as numbers (integers or floats) or words (strings). Typically, these are the elements that will be stored in lists and dictionaries.

An integer is a whole number:

i = 5

type(i)

A float is a number that allows for decimals:

f = 5.2

type(f)

Note that a float can also not have decimals and still be stored as such:

fw = 5.

type(fw)

However, they are different representations:

f == fw

- Lists: a list is an ordered sequence of values that can be of mixed types. They are represented between squared brackets (

[]) and, although not very efficient in memory terms, are very flexible and useful to "put things together".

For example, the following list of integers:

l = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

l

type(l)

Or the following mixed one:

m = ['a', 'b', 5, 'c', 6, 7]

m

Lists can be queried and sliced. For example, the first element can be retrieved by:

l[0]

Or the second to the fourth:

m[1:4]

Lists can be added:

l + m

New elements added:

l.append(4)

l

Or modified:

l[1]

l[1] = 'two'

l[1]

l

- Dictionaries: dictionaries are unordered collections of "keys" and "values". A key, which can be of any kind, is the element associated with a "value", which can also be of any kind. Dictionaries are used when order is not important but you need fast and easy lookup. They are expressed in curly brackets, with keys and values being linked through columns.

For example, we can think of a dictionary to store a series of names and the ages of the people they represent:

ages = {'Ana': 24, 'John': 20, 'Li': 27, 'Ivan': 40, 'Tali':33}

ages

type(ages)

Dictionaries can then be queried and values retrieved easily by using their keys. For example, if we quickly want to know Li's age:

ages['Li']

Similarly to lists, you can modify and assign new values:

ages['Juan'] = 73

ages

Using this property, you can create entirely empty dictionaries and populate them later on:

newdict = {}

newdict['key1'] = 1

newdict['key2'] = 2

newdict

Functions¶

The last part of this whirlwind tour on Python relates to functions, or more properly termed, methods. The motivation is that, so far, we have only seen how you can create Python code that, if you want to run again somewhere else, you need to copy and paste entirely. However, as we will see in more detail later in the course, one of the main reasons why you want to use Python for data analysis, instead of a point-and-click graphical interface like SPSS, for instance, is that you can easily reuse code and re-run analyses easily. Methods help us accomplish this by encapsulating snippets of code that perform a particular task and making them available to be called.

We have already used methods here. When we call np.arange, we are using one of them. Now, we will see how to create a method of our own that performs the specific task we want it to do. For example, let us create a very simple method to reproduce the first loop we created above:

def run_simple_loop():

for i in np.arange(10):

print i

return None

Already with this simple method, there is a bunch of interesting things going on:

- First, note how we define a bit of code is a method, as oposed to plain Python: we use

deffollowed by the name of our function (we have chosenrun_simple_loop, but we anything could have done). - Second, we append

()after the name, and finish the line with a colon (:). This is necessary and will allow us to specify requirements for the function (see below). - Third, realize that everything inside a function needs to be indented. This is a core property of Python and, although some people find it odd, it enhances readibility greatly.

- Fourth, the piece of code to do the task we want, printing the sequence of numbers, is inside the function in the same way it was outside, only properly indented.

- Fifth, we finish the method with a line starting by

return. In this case, we follow it withNone, but this will change as methods become more sophisticated. Essentially, this is the part of the method where you specify which elements you want it to return and save for later use.

Once we have paid attention to these elements, we can see how the method can be called and hence the code inside it executed:

run_simple_loop()

This is the same way that we called np.arange before. Note how we do not include the colon (:) but simply use the name of the method followed by the parenthesis.

This is the simplest possile method you can write: you do not require anything, just executing it, and the code produces and output (the printout) but it is not saved anywhere. The rest of this section relaxes these two aspects to allow us to build more complex, but also more useful, methods.

First, you can specify "arguments" to be passed that modify the behaviour of the method. Remember how we called np.arange with a number that implied the length of the sequence we wanted returned. We can do the same thing in our own function. The main aspect to pay attention to in this context is that the arguments need to be variables, not particular values. Let us see a modified example of our method:

def run_simple_loopX(x):

for i in np.arange(x):

print i

return None

We have replaced the fixed length of the sequence (10) by a variable named x that allows us to specify any value we want when we call the method:

run_simple_loopX(3)

run_simple_loopX(2)

Another way you can build more flexibility into a method is by allowing it to return an output of the computation. In the previous examples, the function performs a computation (i.e. printing values on the screen), but it does not return any value. This is in contrast with, for example, np.arange which does return an output, the sequence of values:

a = np.arange(10)

a

Our function does not save anything:

b = run_simple_loopX(3)

b

We can modify this using the last line of a method. For example, let us assume we want to return a sequence as long as the series of numbers we print on the screen. The method should be:

def run_simple_loopXout(x):

for i in np.arange(x):

print i

return np.arange(x)

Note the main difference: instead of returning None, we are telling Python to return a sequence, which has the same length as the one used to specify the loop. Now, there is an alternative way of being more efficient in this method, and that is assigning the sequence to a new object and using it when necessary later on. The results are exactly the same, but there are less computations performed and, more critically, we minimize the chances of making mistakes.

def run_simple_loopXout(x):

seq = np.arange(x)

for i in seq:

print i

return seq

Either of these two new versions of the method return an output:

a = run_simple_loopX(3)

b = run_simple_loopXout(3)

a

b

The advantage of methods, as oposed to straight code, is that they force us to think in a modular way, helping us identify exactly what it needs to be done, in what order, and what it is required. Encapsulating these atomic bits of functionality in methods allows us to write things once and flexibly use them everywhere, saving us time (and headaches) in the long run.

A final note on functions. It is important that, whenever you create a function, you include some documentation about what it expects, what it does, and what it returns. Although there are many ways of doing this, the typical convention is as follows:

def run_simple_loopXout(x):

"""

Print out the values of a sequence of certain length

...

Arguments

---------

x : int

Length of the sequence to be printed out

Returns

-------

seq : np.array

Sequence of values printed out

"""

seq = np.arange(x)

for i in seq:

print i

return seq

Documentation, as any string, are highlighted in red on a notebook. Let us have a look at the structure and components of a well-made documentation (also called "docstring"):

- It is encapsulated between triple commas (

"""). - Begins with a short description of what the method does. The shorter the better, the more concise, the even better.

- There is a section called "Arguments" that lists the elements that the function expects.

- Each argument is then listed, followed by its type. In this case it is an object

xthat, as we are told, needs to be an integer. - The arguments are followed by another section that specifies what the function returns, and of what type the output is.

Documentation in this way is very useful to remember what a function does, but also to force yourself to write clearer code. A bonus is that, if you include documentation in this way, it can be checked with the standard help or ? systems reviewed above:

run_simple_loopXout?

help(run_simple_loopXout)

Exercise to work on your own¶

Write a properly documented function with the following behaviour:

- It has a meaningful name (i.e. it is related to its behaviour).

- It takes an integer that represents the length of a sequence that will be created.

- It creates a dictionary that is empty.

- It loops over the sequence and stores each number as the key of an entry in the dictionary, assigning either "odd" or "even" to the value, depending on the type of number.

- Returns the dictionary.